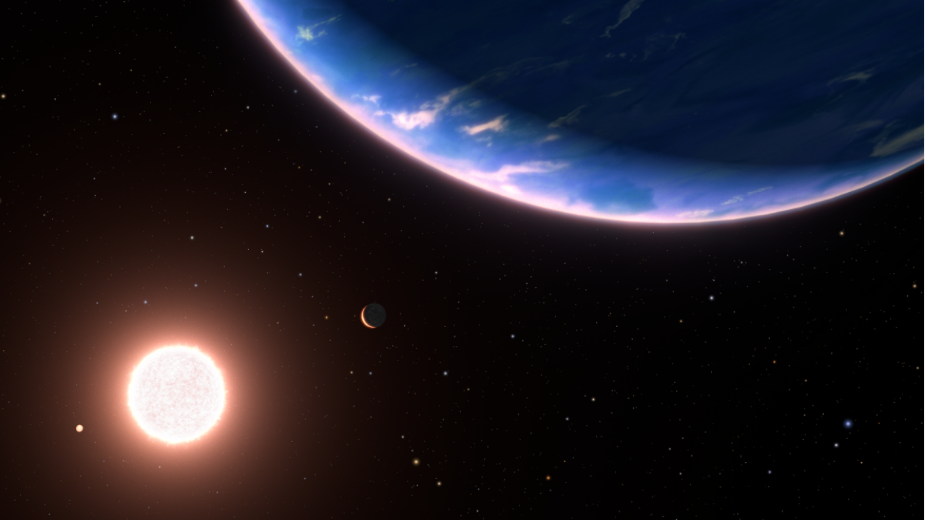

Scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have discovered what some are calling the first clear evidence of a “steam world”—a planet enveloped in wet heat—located approximately 100 light-years from Earth in the constellation Pisces.This new finding adds to the existing catalog of over 5,700 confirmed exoplanets outside our solar system, which include ice worlds and water worlds.

The exoplanet, known as GJ 9827 d, is roughly twice the size of Earth and boasts an atmosphere predominantly composed of water vapor.

This discovery marks a significant milestone, as such worlds were only theorized to exist until now. “It was a very surreal moment,” said Eshan Raul, who contributed to the research while an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan.“We were searching specifically for water worlds because it was hypothesized that they could exist. If these are real, it really makes you wonder what else could be out there.”

Scientists envision that this steam world has a thick, water-rich atmosphere, with a surface free from ice or flowing water.Researchers suggest that GJ 9827 d resembles what icy moons of Jupiter, such as Europa and Ganymede, might be like if they orbited closer to the sun instead of in the outer solar system.

With an estimated surface temperature of 660 degrees Fahrenheit, GJ 9827 d orbits its host star at a close distance.In comparison, Earth’s average surface temperature is a much cooler 59 degrees Fahrenheit. Due to the exoplanet’s extreme heat, its atmosphere likely comprises a mix of gases, lacking clouds or distinct layers.

While signs of hydrogen-rich atmospheres have been identified surrounding many gas giants like Jupiter, the quest for a terrestrial world with a protective atmosphere of heavier elements had proven elusive until now.

Caroline Piaulet-Ghorayeb, a doctoral student at the University of Montréal and lead author of the new study published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, confirmed that this is the first verified case of an exoplanet atmosphere where hydrogen is not the dominant component.

Since its launch, the JWST has frequently employed transmission spectroscopy to analyze exoplanets. This technique involves studying starlight filtered through the atmospheres of these worlds as they transit their host stars.

Molecules in the atmosphere absorb specific wavelengths of light, allowing astronomers to identify missing segments in the spectrum—akin to creating a rainbow—to reveal the molecular composition of the atmosphere.